I found this

week’s lectures and readings quite fascinating because until now I had never

seen the connection between medical technologies, such as the x-ray or the MRI,

and art. As Victoria Vesna retrospectively notes in Medicine pt1, only years after her tedious art classes that

revolved around the human anatomy did she realise that this knowledge “proved

to be critical for the work that [Vesna] was doing”.

|

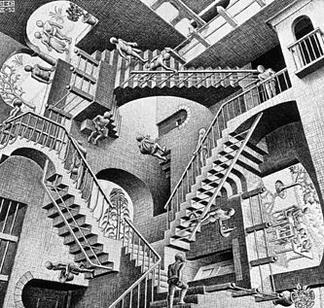

| Figure 1 - Photo of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, discoverer of the X-ray http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_R%C3%B6ntgen#/media/File:Roentgen2.jpg |

Another example of

art using medical technologies and knowledge as inspiration on works on the

human body is the travelling exhibition “Body Worlds”, developed and promoted

by Gunther von Hagens. Its works focuses on a process known as “plastination”

which “is a technique…used in anatomy to preserve bodies or body parts”

developed by von Hagens in 1977 (Wikipedia).

Having seen the exhibits myself, I could not help but feel conflicted between

horror and fascination. Through these exhibits, I feel that the human anatomy

can be somewhat dumbed-down for the general public to see and understand for

educational purposes; on the Body Worlds website, Von Hagen confirms this as he

hopes “for the exhibitions to be places of enlightenment and contemplation”. As

I was quite young, I didn’t have much understanding or interest in these works,

but now I have a much deeper admiration for von Hagens’ amazing albeit weird

innovation.

|

| Figure 2 - An example of an exhibit from Body Worlds examining the "cycle of life" http://i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/01014/body_worlds_pregna_1014471c.jpg |

However, while

medicine and technology allow artists to closely examine and understand the

human body, it was in fact art that allowed medicine and technology to thrive

in the first place, as we see from the beginnings of human dissections. Vesna

notes that artists played a “critical role” in the first human dissections,

helping doctors and researchers to document the progress and understanding of

the body by visualising and recreating images of the body’s internal structure.

Thus, it can be concluded that without art, not only would our understanding

and knowledge of the human body be severely limited, but also hinder the

progress of technological advances in medical procedures.

|

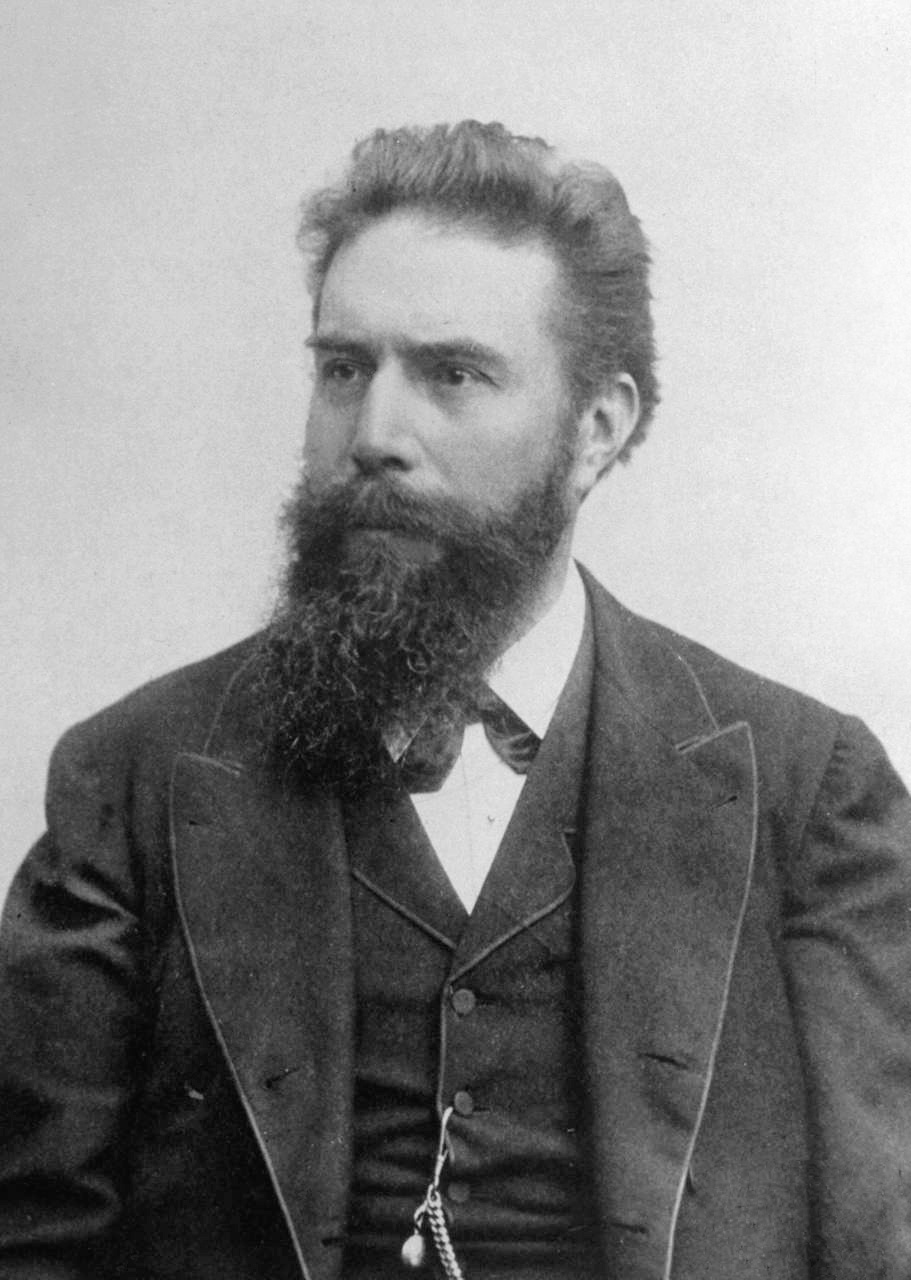

| Figure 3 - Cover of Gray's Anatomy, extremely influential anatomy textbook written by Henry Gray |

A more modern

example of how art can be used to aid medicine and technology can be found in

Donald Ingber’s The Architecture of Life.

In his book, the way he describes the body is much like how an architect

describes a building; in fact Ingber notes how “both organic and inorganic

matter are made of the same building blocks” (48). His understanding and

knowledge of architecture has allowed him to view the human body in ways that

many could not see; Ingber’s “early scientific work led to the discovery that

tensegrity architecture…is a fundamental design principle that governs how

living systems are structured” according to Wikipedia.

Citations

- Medicine Pt1. Perf. Victoria Vesna. Youtube. N.p., 21 Apr. 2012. Web. 25 Apr. 2015

- "Plastination." Wikipedia. N.p., 13 Apr. 2015. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plastination#History>.

- "A Life in Science - Gunther Von Hagens." Body Worlds. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://www.bodyworlds.com/en/gunther_von_hagens/life_in_science.html>.

- Ingber, Donald E. The Architecture of Life. N.p.: Scientific American, 1997. PDF.

- "Donald E. Ignber." Wikipedia. N.p., 7 Apr. 2015. Web. 25 Apr. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_E._Ingber>.